Prior to 1870, industry in the United States was not an integrated whole, but a sum of many heterogeneous parts spread across multiple regions. Attempting to study the economy as a whole is difficult because data is scarce, however, studying important industries in each region during a period of rapid change serves a purpose. Fortunately, rapidly changing industries or those heavily concentrated in specific regions tend to keep business records.

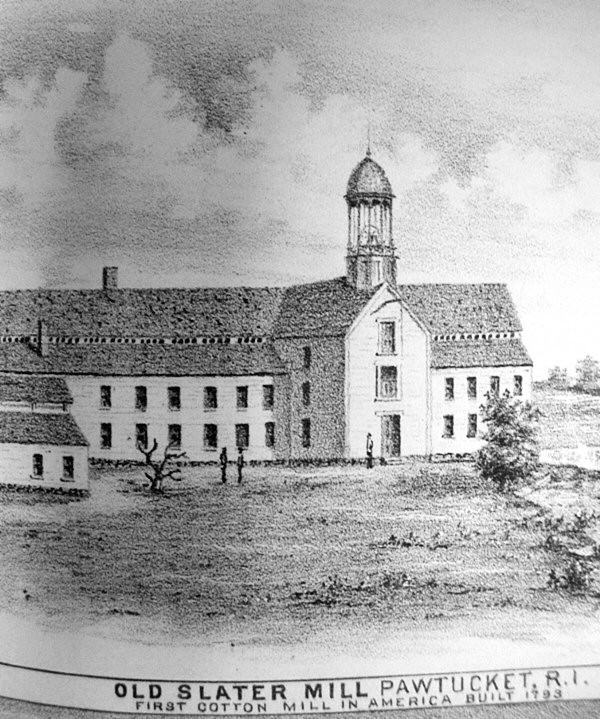

The cotton textile industry provide a fine example of what can be achieved using a regional approach. Cotton textile industry was heavily concentrated in the New England area and growth after 1820 was associated with the rise of a particular set of firms. There were two principal types of cotton textile firms in New England.

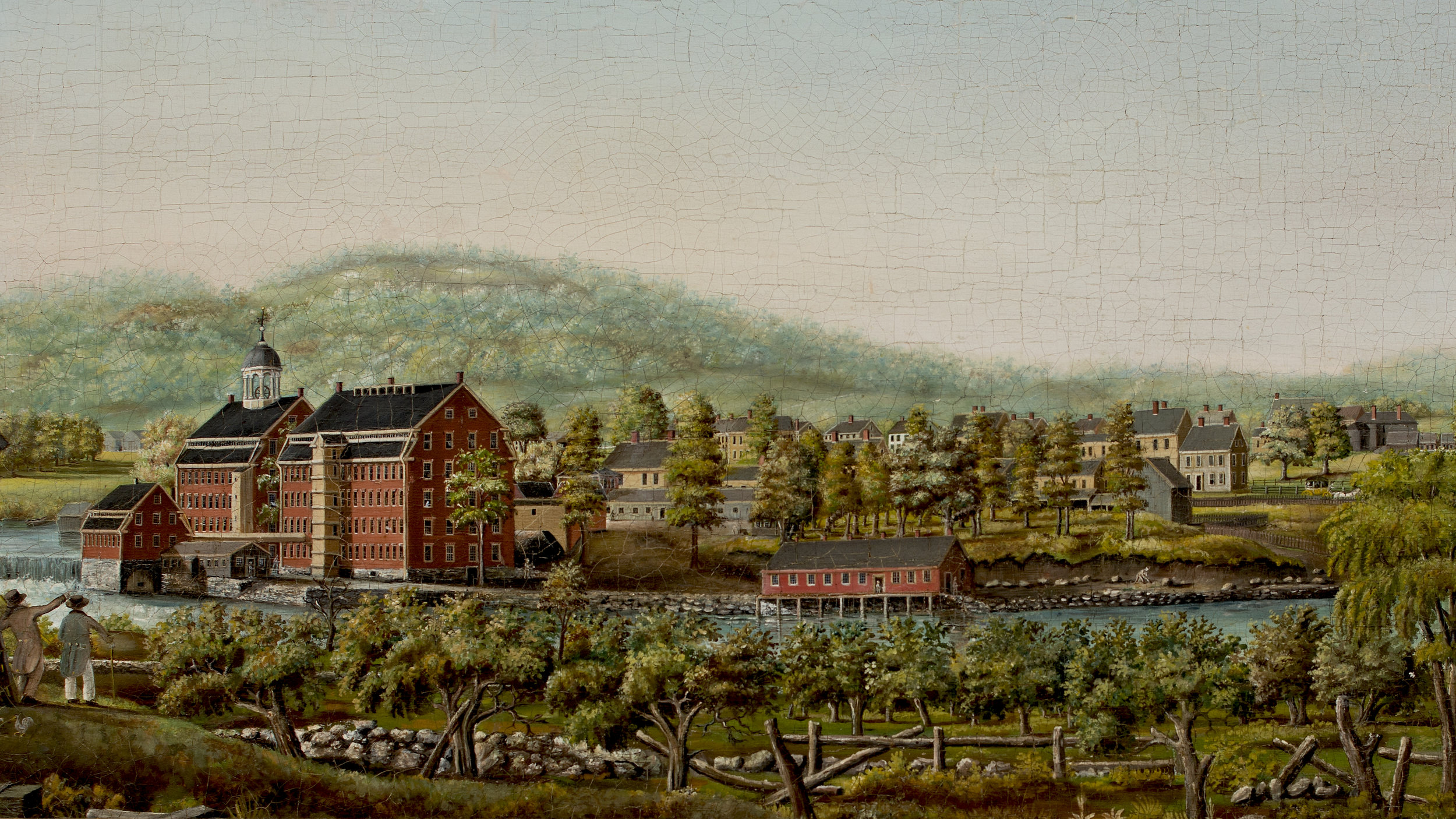

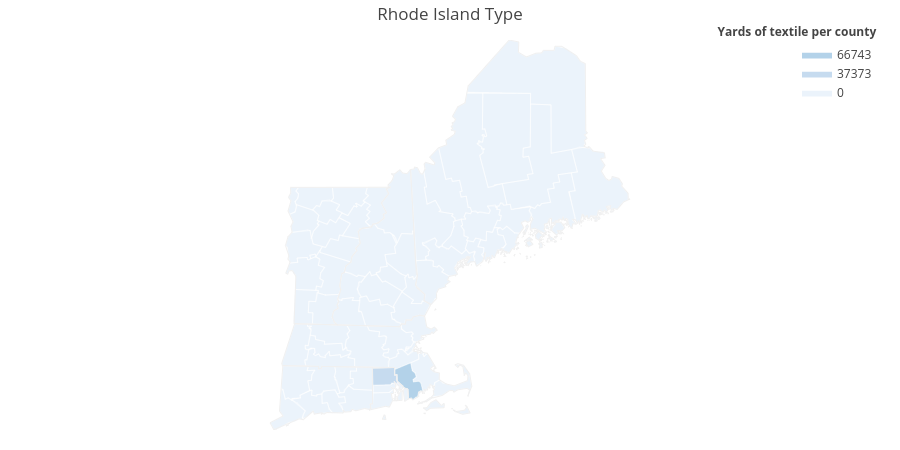

The firms of the Massachusetts-type, modeled after the Boston Manufacturing Company, were located on major rivers of northern New England. Generally capitalized in excess of $500,000, these were typically multi-factory operations. From the beginning, Massachusetts-type firms were fully integrated facilities producing units heavily concentrated in low-count goods or goods that drop in demand when consumer income rises. Massachusetts-type firms were responsible for the majority of textile producing from 1825–60 measured in yards.

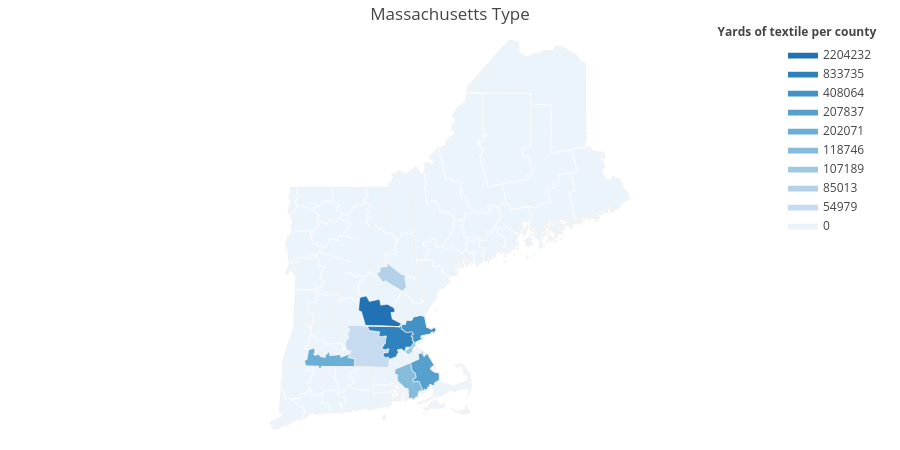

The image above shows the amount of yards of textile produced per county in the New England area.

Rhode Island-type firms, existed along side the Massachusetts-type in much a much higher number of operations. Rhode Island-type mills were small, often specialized, and tended to produce medium grade cloth. These firms were responsible for a relatively small amount of total textile production from 1825–60 measured in yards. The image below shows the amount of yards of textile produced per county in the New England area.

The distribution of these firms were not wholly geographic. In some cases, the firms of Rhode Island-type were located in Massachusetts as well as Rhode Island Connecticut. Company records for at least some of the Massachusetts-type and Rhode Island-type firms exist for at least some part during the antebellum period.

Increase in productivity by Massachusetts-type firms during the antebellum period resulted in an increase in output per spindle by approximately 50 percent during the 1830’s. In the long run, an upward trend of labor productivity and changes in direction of capital-index around 1840 might suggest innovation prior to 1840 was labor saving as well as capital saving.

It is frequently cited that the American textile industry underwent a revolutionary transformation in the decade between 1814 and 1824, but that thereafter technical progress was relatively slow. The decade saw inventions and widespread innovation of the power loom, Walter dresser, the double speeder and filling frame, self-acting loom temple, number of picker and openers and the increase in spindle speed associated with the innovation of the belt drive. Moreover, new machines do not tell the full story. More important, new refinement were worked out in the machine shop and incorporated in the latest model of machine. In terms of industrial organization, the integrated mill, successfully pioneered by the Boston Manufacturing Company, was widely adopted. The graphic above shows that the industry leaders, i.e. Massachusetts-type, integrated machine shops, which actually developed new machines and improved existing one were able to out product Rhode Island-type mills.

The dominant economic event of the late 1850’s was the panic of 1857. Sales and output began to erode early in that year but dropped swiftly during the last half. The year-end inventories were almost twice the level of 1856. The Panic of 1857 was a financial panic in the United States caused by a decline in international trade at a time of over-expansion in the domestic economy.

The records of business firms represent a relatively untouched resource which should be of use to study the American economy. This post attempts to make sense of the fluctuations in the cotton industrial output between the Census benchmark years. These records can shed light on the fluctuations in inventories, sales, costs, profits, and for other variables for which there is only benchmark data.

Reference

- Lance E. Davis and H. Louis Stettler III. The New England Textile Industry, 1825–60: Trends and Fluctuations, pages 213–242. NBER, 1966.